A podcast I’ve taken note of is one by Chris Williamson. A clip featuring Douglas Murray on Williamson’s Modern Wisdom podcast was entitled “Most People are Cowards.”

In that discussion, Williamson told a story about an acquaintance who did the “manly stuff,” the hard workouts, putting himself in difficult situations of various types, who confessed that he’d always worried that he was a coward. It was the tale of the person who believed he was cowardly running toward the battlefield.

That’s not altogether unheard of, kind of like aversion therapy. Paraphrasing from the video, it went like this: “My entire life I was afraid that I was a coward. In my darker moments, I could hear my better self … clearing his throat in the room next door.”

An interesting take, the individual had faced “cancellation,” being shunned by his in-group or something. He realized this was his test. When that negative outcome arose, he told Williamson that his “better self in the room next door” just kicked that door in and came on in to help.

I think a lot of us have that “better self” and don’t always recognize it. As the discussion went on, the issue of post violent event trauma or PTSD, along with the observation that it seems to dwell in those suddenly dropped into a life-threatening situation. For those who voluntarily walk into danger, Murray noted, it appears less common.

Murray noted that danger through personal choice –volunteering -- versus situations you find yourself thrust into are remarkably different in terms of the post-event outcomes; the situations you’ve been thrust into seem to have a higher likelihood of PTSD (assuming you survive, I add) than if you choose to enter those situations.

I’ll note that Cooper seemed astonished at the concept of post violent event trauma, he called it POT – post-operational trauma – having never occurred to him and not having heard of its incidence. There’s a reason that we can go into.

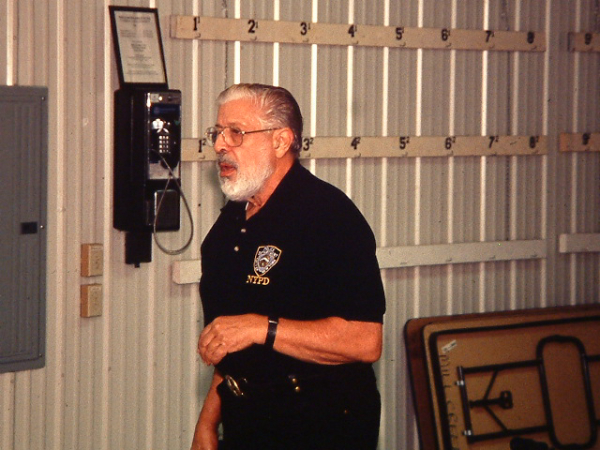

With Jim Cirillo, he described his fear in those situations as they arose. Only a moron wouldn’t be afraid. But he was too busy to dwell on the fear in the midst of the fight; he had things to sort out first then he could give into the fear. His encounters on the Stakeout Unit were, clearly, events he chose to attend; though he didn’t know they would happen in a particular shift, he was going into high-incidence armed robbery locations and setting up, like a hunter in a ground blind. That he was a well-adjusted individual with a sunny outlook, a great sense of humor and a strong family bond was icing on the cake.

With Cooper, his mindset program – designed to overcome the natural resistance to causing harm to other human beings – had the side benefit of having “chosen (in advance) to enter (or avoid) the situation,” perhaps as Murray notes, minimizing the onset of negative mental issues thereafter.

I don’t know.

If you’re afraid of being a victim of violent crime (not paranoia, that hinders living life, but a nagging doubt that you’d be able to handle it), what do you do about such situations?

Do you join the cops? It makes the least sense, or so it seems to me, or perhaps it’s a selection due to a lack of courage. Step into it, face it head on.

Maybe they have something here.

— Rich Grassi