During a search for other material, I came across a substack page I’d been unaware of, FUNshoot News. Written by John Buol, Editor of American Gunsmith, the very first story I landed on was “Field Shooting Accuracy Study,” his report on a piece previously run in Policing: An International Journal, entitled “Hitting (or missing) the mark: An examination of police shooting accuracy in officer-involved shooting incidents.”

In short, the study was an analysis of 149 shootings reported over 15 years by the Dallas Police Department. The authors were dismayed at the relative inaccuracy of service-related shootings by members of the service.

John is no duffer; his experience is clearly long and varied, including impressive competition shooting accomplishments.

He quotes the research team and their claim that “although the amount—and quality—of firearms training received by officers over the last century has increased considerably, there appears to have been little improvement in shooting accuracy.”

Any of you who are in-service (or prior service) buy that? Agency training is – charitably – all over the map, from nonexistent to marginal.

I won’t review John’s piece, but you should. It doesn’t matter if you’re a badge, private security contractor, military member of service or armed citizen, you’ll find this material provokes thought about the issue, “how much, what kind and of what frequency types of training are necessary for success in battle?”

Before going any further on police shootings, it’s important to note that the majority of (reported) non-LE shootings feature victims who put hits on victim offenders regardless of having any training or skill (on either side).

Understand that it could have been the marginal offender getting too close too late in the game, it could be bad luck for the crook and good luck for the citizen, the offender’s weapon failed to work … in short, there is a mountain of intervening variables.

Likewise in police shootings, except the potential variables increase. Trying to force a ‘one size fits all’ combatives training with the expectation of success is silly. I’ll be trying to take some of this apart over time; this feature is just a start. We’ll start with what do we have to know?

In my old agency, we used a range of training methods, from the apparently useless to the extremely hands-on. Which worked the best?

Yes.

A nonsensical answer? No, a precisely delivered answer.

Example: Faced with the daunting task of pulling people off of the road for the required 40 hours of annual in-service, the state academy of the era allowed a percentage of the ‘training’ to be accomplished via video – as long as there was a written test or “meaningful discussion.”

That ain’t training.

Still, I was one of those elected as a “shift trainer,” so I was saddled with providing the video bits. Taken from dash cam videos and sold commercially, I found the provided commentary to be largely useless except as a springboard to disagree and generate some arguments within the group of trainees. One case had a surprise, the offender had a knife no one saw. This generated talk of approach tactics and the danger of the ‘marginally compliant’ or reluctantly compliant suspect.

A few weeks passed and a kid from the overnight shift grabbed me in roll call. He was obviously overwrought – I found out he was coming down from an extreme adrenaline dump. That very video and the talk afterwards was fresh in his mind when he stopped a suspicious pedestrian on the highway. The air was busy and he couldn’t report the stop immediately. The suspect was noncompliant and the officer forced a control in distance, preventing the suspect from closing on him. He finally used the threat of gunfire to stop him.

When help got there, they found the machete that he’d quickly discarded.

“If it wasn’t for that video,” he said, “I’d have just walked up on him.”

That’s not a shooting story. That’s a successful contact story, successful due to maintaining distance and using obstacles, being wary – anticipating danger – and using convincing language (“Take another step and you’re dead.”) He was safe and alive – as was the offender.

The deputy could well have shot. I knew him then and, even with the dark environment except for patrol car lights and the lights of passing traffic, I figure he’d have made the hit.

The concern of the researchers was less on how to manage potentially lethal close-range encounters and more on “unintentional hits” on the street, a valid concern. I believe that far too much of firing range experience is made up of how quickly one can make repetitive shots in a sterile environment. Far too little is made of competent gunhandling and disciplined, deliberate shooting.

It’s less “what’s your best split time” and more “what’s your quickest time to a decisive first hit?” Or it’s “Can you hit 100% for sure at this distance?” And that’s the point … if it’s down to shooting.

I trained a group of new instructors for a few days before I retired. Their class graduation exercise was different from the things I’d done in previous instructional outings. As my agency business cards were “expiring,” I made a vertical cut in the top of each target backer, placed a business card in each one and stood the instructor trainees at a measured 24 feet from the front edge of the card.

They were dismayed that they had to hit the cards on edge, but I was going to allow them up to five rounds to do it. I discussed the ‘card trick’ with them, and told them how I calculated the best way to make that hit at eight yards. Then they each shot individually, so the others got to watch.

A little pressure?

No one took more than three rounds, a good number hit it on the first try.

Were they capable of that precision on the street?

Consider that the card wasn’t moving, not a human being. It wasn’t shooting back. The backstop here was a berm in front of a large raised area of landfill – not a crowded street, the interior of a convenience store or mobile home, each potentially with uninvolved human beings as the backstop.

No one is capable of that precision in that environment. Not consistently.

You’re just human.

The rule is, only fire the shot you know you can make. If there’s any doubt, don’t fire it out. It’s not that you made a loud noise – and forget “laying down cover fire.” This isn’t Khe Sanh and it’s not Fallujah. It’s your town with your citizens.

How do you determine what shots you can make, with 100% certainty? You check that in the sterile range environment. If you can’t do it there, don’t try it out in the world. The standard walk-back drill is worthwhile in this analysis. As a baseline – something of which you should have a solid grasp – it has few peers.

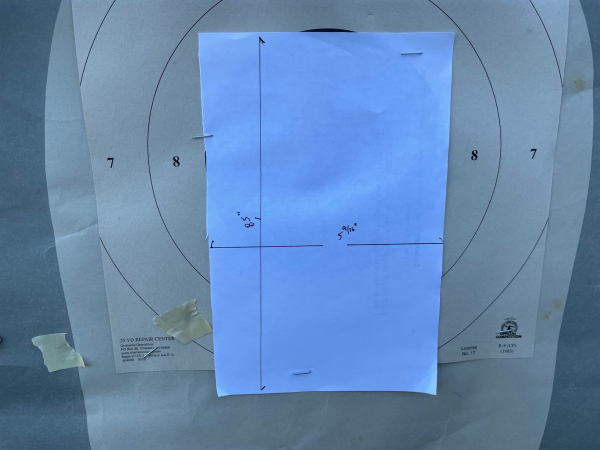

Staple up the target of your choice (not a huge FBI-Q, but something of value; a B-8 repair center is fine or simply fold a sheet of copy paper in half). Start at a reasonable distance, but not so close that minor errors are forgiven; say 21 – 30 feet. Print a deliberate pair at the close distance. It’s smart to mark the hits, then back off to the next further distance. Do it again.

This is just marksmanship, plain and simple. You’re testing your ability to hit a mark, nothing else.

How far back do you get when you drop off the paper? Make a note, mark the target, then go back to that distance and try it once more. Did you make it?

Mark it, step back to the next distance and try again.

Once you know where it goes into the ditch, record that. You know where your work needs to begin strictly in marksmanship. You also know that you’re likely a solid shooter operationally at ½ - ¾ of that distance – if you’re ready, you know that a fight is coming and there are no non-hostiles in front of the muzzle.

Smart training – doing progressively more difficult drills – will help you see that distance increase, as your competence increases. As competence increases, so does confidence.

It never ends until you do.

-- Rich Grassi