Last time, we discussed the issues relating to minimum levels of competence in defensive gun use in terms of the public’s willingness to train, a feature that tracks along with the relative apathy seen in administration as well as uniformed members of service in law enforcement; it’s mostly a “checked the box” arrangement, doing the minimum.

Our concern is more “doing the most likely needed, then moving on up.” So what do they need? We could start here:

1. Defensive gun uses always begin (on the defender’s side) with access to the firearm from place of storage or the holster (if worn) – after the defender realizes there’s a problem. Awareness and mental conditioning is another problem, category B, if you prefer; critical to success but outside the scope of this discussion.

2. The defense gun use requires reasonable accurate speed of delivery – not a “mag dump,” but a dedicated cadence of fire as needed.

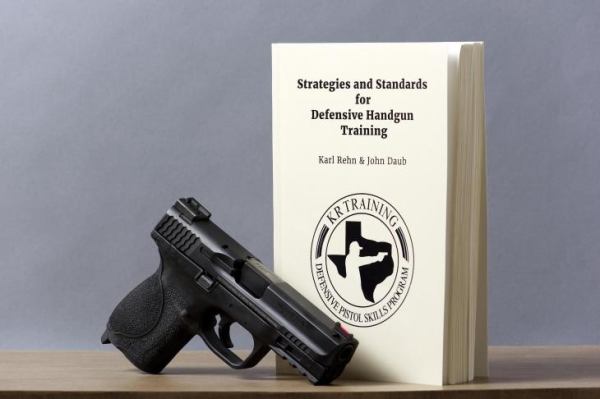

From our source material, Strategies and Standards for Defensive Handgun Training (Columbia, SC: 2019), Karl and John use analysis from Tom Givens, a “gun fit” drill from Gila Hayes (Armed Citizens' Legal Defense Network) and the Texas License to Carry qualification course – a less-than-terrible effort at actually testing some gun skills (with the target they originally used, not the NRA B-27).

The discussion takes us along through analysis to this conclusion: drawing the gun (or otherwise gaining access to it), placing multiple hits into a small area from “close range,” quickly, using both hands – or maybe one hand or the other.

That’s not a bad summation at all and reflects what we’re seeing in actual defense gun uses that require the firing of rounds at an assailant; remember, there are many defense firearms applications that require only the appearance of the gun – with no fired rounds necessary – for the offender to break contact.

We’ll take that. We can’t bank on it, but when it happens it’s a wonderful success.

When we look at their attempt to ‘refit’ the Texas course of fire, we quickly notice they have some stages from “ready” (guard). This is relevant if you don’t believe in gun pointing people – which would make you wise indeed. Having the muzzle directed into the deck off-threat, but using the appropriate verbalization (another vastly undertrained skill) and body language (which everyone reads, but few can completely describe) do more to convince the offender of your intentions than having him look down the muzzle.

It seems that some offenders relish having guns pointed at them. I’ve seen some smile at the effort, knowing that the armed person won’t pull the trigger – intentionally.

Brave. Stupid, based on the likelihood of negligent discharge, but brave nevertheless.

Having the gun ready to shoot, low ready (guard), index finger at high register, then being able to quickly deliver hits into the center of the threat is a relevant skill. Dave Spaulding, Handgun Combatives, has such a component in his training:

“I begin some of my courses with several “time in” drills in order to evaluate each student’s skill sets. My time in drills are fired at 20 feet into a 6 x 10-inch rectangle as follows:

• One shot from the ready position of their choice in one second; ?

• One shot from the holster in two seconds; ?

• One shot, emergency reload, one shot in 3.25 seconds;

• Four rounds from ready in two seconds”

Now we’re getting to it – the reload requirement is subject to debate, but it sure can’t hurt to know it and be able to perform it. As the authors point out, a good many ranges don’t permit holster use – few instructors have any certification to teach it – and those ranges are often allowing the cadence of “one round per second.”

This doesn’t help someone who’s trying to see how fast he can accurately hit before “the wheels come off” – and that’s a handy bit of information to have.

“Should training – and a “test” – be required by law?”

Expecting the government to solve problems is silly. It never has yet. Government is singularly unable to actually solve problems. It’s handy to do those things that profit-making enterprises can’t profitably do well. It has a very narrow range of relevance – meaning it’s gotten far too big for its brief. In short, “no.”

The time investment issue in training rears its ugly head; so you have the desire to train? Who can take the time off from work, the family, household chores, social activities, and worship to run around with guns all day? Besides, it amounts to cramming lots of information into short time frames. It’s drinking from the firehose.

Better to take regular, routine sips of water over longer time: better for hydration, better for learning and skills acquisition.

The costs of the industry standard training enterprise are large: travel costs (transpo, lodging, chow) plus the costs of gear, ammo, tuition, range fees, all add up. Our Tactical Professor, also mentioned in our source book, has proposed (and offered) local 2-3 hour training segments. KR Training, the company of our source’s author, offers low cost training blocks, 3- and 4 hour segments in series, which accumulate to the forty-hour defense pistol skills program – and includes requirements for the Texas LTC certification.

That’s very smart. Deeper learning occurs if spread out over time in smaller segments. I’d written about such a program I’d created for law enforcement in the 1990s in an article “The Case for Monthly Firearms Training,” published in Law & Order Magazine. It’s not a new idea, it’s just contrary to the “reasoning-resistant” among us.

The essentials for this “piece work” include elements not available when I penned that article as well as component parts that we’ve always had. A ‘blended learning’ approach with book-work being incorporated into online training – like the Texas concealed carry program – frees up physical skills time on the range.

Using an old staple of any physical skills education – prioritizing skills – means that students learn a technique then reuse it for chained multiple-skills tasks, like having a high-ready position as a component of the draw stroke.

What minimum competency? “A drill which you can complete cleanly (zero misses) on demand.” It’s something not used for licensing, but for personal assessment.

Competent for what?

Distance,

Environmental factors,

And, engagement: threat(s), rounds fired.

For Tom Givens, a source for our source book, that means a robbery of some type, one-two assailants, from three-to-seven yards; 3 shots, 3 steps in 3 seconds – more or less. Karl Rehn further explained it as multiple hits in a small area from close range – quickly.

What don’t you need?

More appropriately, what could be emphasized less or moved back in the defense pistol program? Shooting on the move is one thing; Paul Howe, retired US Army Special Forces, still teaches to either move or shoot – and he’s got some experience in this thing. He plants his feet to shoot, then moves as quickly as he can. The “speed reload” – we’re seeing no cases where a reload “saved the day.” Still, it’s poor form to finish a battle with an empty firearm.

The only way you know the fight is over is when they’re stringing crime scene tape.

Clearing stoppages? That looks like a class the bad guys could use – but I’m glad they don’t practice it. If you get the wrong gear, you could get all the “immediate action” practice you could ever want, but may have little confidence in your equipment . . .

The “minimal” skills? Presentation from concealment (or place of storage), shoot with two hands, shoot with one hand – right and left. Reloads and malfunctions practice are nice to have. I’d add load, unload, and post-shooting procedures to the need category.

Start out by achieving that minimum competency standard. Then you can work on exceeding it.

- - Rich Grassi