Editor’s Note – This is not a revolver story, but if you’re interested in revolver content, let us know – at info@thetacticalwire.com with “Revolver Special Edition” in the subject line. It’s been some time since we ran a special edition. It may be time to do one now. Let us know –

The history of the American firearms industry is not a story that embodies the idea of stability; it's been a bumpy ride. Four major American manufacturers (Colt, Smith and Wesson, Remington, and Winchester) have oscillated between feast and famine almost from their origins. Economic fluctuations, gearing up for periodic war-time production followed by a precipitous fall in demand, and just plain bad management left them constantly living in the shadow of potential bankruptcy.

Now CNC driven manufacturing can produce firearms with more precise tolerances than the hand-tooled production of the past in a fraction of the time. However, it’s at the cost of a corresponding demise of individual mastery and craftsmanship. Compare a pre-war, commercial Colt 1911 with a current standard grade Colt or a S&W Registered Magnum with a standard grade current production Smith, and you’ll see what I mean. On the production side of the industry, craftsmanship is mostly limited to the “boutique” manufacturers (i.e. the Brown’s, Baer’s and Wilson’s of the world). Fortunately, individual mastery is still alive in the gun business, but pretty much solely in trades such as custom stock makers, engravers, and gunsmiths whose success and continued existence depends upon their personal competence.

One such master craftsman is Nelson Ford, dba “The Gunsmith, Inc.” in Phoenix, Arizona. Nelson is a graduate of the Colorado School of Trades and has been a full-time self-employed gunsmith since his graduation in 1980. The curriculum for the school was rigorous. Failure is a great teacher and according to Nelson, “you gotta screw up a lot of stuff in order to get good.” Finding out what won’t work is a large part of the learning process; diagnostic skills are as necessary as mechanical ability for a professional gunsmith.

I was introduced to Nelson by my friend Matt Olivier at Phoenix’s Cowtown Shooting Range. Once a week, Nelson goes to the range with three or four briefcases full of handguns that he’s worked on to test fire them for reliability and accuracy. No gun leaves his shop without his personal knowledge that his customer’s life will not be jeopardized by a malfunctioning firearm that he’s worked on.

His reputation in the industry was built around his work on Smith and Wesson revolvers. While he loves owning, shooting, and working on Colt 1911s and Single Action Armys, he won’t work on double action Colt revolvers unless he knows the owner (and likes him). His first love is for Smith and Wesson revolvers, with his favorite being the K-22. According to Nelson, “the K-22 is the life blood of every young competitive shooter, they teach you to keep the sights on the target thru the duration of the trigger pull; single action shooting won’t teach you that.”

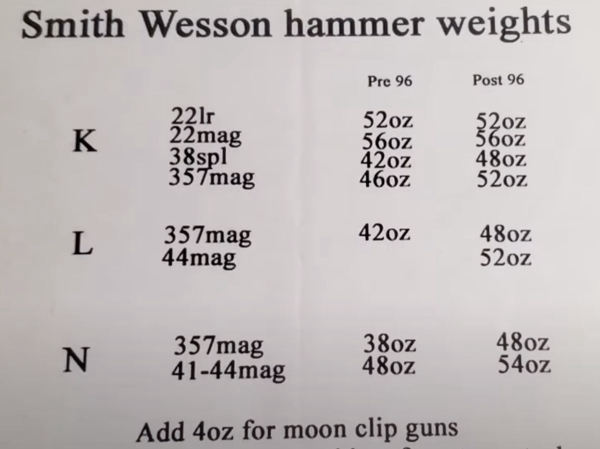

He says that there’s not a lot of difference in working on J, K, L or N frames since most of the internal parts other than hammers and hands are the same and, for the most part, they function identically. Every handgun is different, and performing the same action job or trigger work varies from gun to gun; what takes one hour to accomplish on one pistol can take 2 or 3 hours on another of the same model. Upon occasion a particularly recalcitrant specimen comes through his shop that tests his diagnostic skills. Those rare pieces require incremental labor where he works on it for a while and then puts it aside to do a simpler task on a more cooperative gun while his subconscious is chewing on the problem. “Sometimes I’m sitting at a stop light and I go, ‘hey, I know what’s wrong with that gun’…. when I was younger, I’d occasionally go to the shop at 4 in the morning to get back on something because it was on my mind and what was wrong with it just came to me while I was sleeping.” That type of intuition is developed by years of trial and error.

Part of Nelson’s intuitive understanding of the history, ergonomics and tactical efficiency of firearms comes from a long background of competitive shooting in multiple disciplines. He has shared the shooting range with Rob Leatham and Terry Allison and had shooting dignitaries like Smith and Wesson historian Roy Jinks in his shop; few people can challenge his insight into the use or history of the Smith and Wesson revolver.

I had been confident in my basic knowledge of revolvers. When he explained end-shake corrections and proper head space and flash gap dimensions (.004” for the gap and .010” or under for head space) I was able to keep up with him. Then we got into a discussion on timing the action. As he started explaining the difference between Colt’s step-hand (a holdover from the Single Action Army) and Smith’s bypass-hand, the discussion was quickly over my head. When he transitioned into the differences of disassembling a Smith cylinder versus a Colt cylinder, he might as well have been speaking in tongues. He truly is a walking encyclopedia of revolver specifications.

Most impressive to me however was not the depth of his knowledge but the spectacular examples of his work; I shot some of his guns. To be superlative, a double action trigger pull doesn’t need to be light. It, like good bourbon, needs to be consistent and smooth. I shot a Smith Model 66 that he had tuned and the trigger moved like warm butter on hot glass. No stacking and no glitches, just one consistent flow to ignition. I was hooked. Since that day, I’ve had Nelson work his magic on two Smith Model 19’s, a 66 and a 60. Now my goal is to have at least one Nelson Ford Smith and Wesson to leave to each of my grandkids -- they’re heirloom quality.

Nelson’s talent isn’t limited specifically to Smith and Wessons or even to handguns in general. He’s also an aficionado of Marlin lever action rifles. Since being purchased by Ruger, the quality of Marlin rifles has taken a quantum leap for the better. However, there is an abundance of late production, pre-Ruger Marlins that, to be kind, can best be described as “crude.” I took one such rifle to Nelson and asked him to do whatever he felt was necessary to the gun. Upon completion, he returned to me a rifle whose action is so smooth that the lever can be manipulated with one finger. I followed up that initial subject rifle, a Model 336 in .30/30, with a Model 1894 in .44 magnum; the results were identical.

The gun industry has been gravitating toward plastic and black guns since the 1980’s. Their modularity lends itself to replacing parts rather than “fixing” “fabricating” or “fitting” them. Parts replacement requires little of the skill and none of the craftsmanship demanded to fix, fabricate and especially fit parts to work superbly. In the past couple of years there has been a notable resurgence in revolvers as well as lever action firearms, both of which require occasional fixing, fabricating, or fitting; therefore, the demand for craftsmanship will see no decline soon. The benchmark of future revolvers will be largely set by master craftsmen like Nelson; we need more gunsmiths of his ilk, and they’re a diminishing breed.

Not one to shy away from voicing his opinion, Nelson has started posting YouTube videos in which he describes his methods for working on specific handguns. He pulls no punches in critiquing traditional opinions by way of demonstrations and anecdotal examples from 45 years of experience. Subjects include the Colt Python and V Spring Actions, 4 videos on the 1911 including trigger work and feeding as well as 2 videos on S&W K frame spring weights, cylinder alignment, internal parts and cylinder spacing. The videos are educational and will hopefully inspire fledgling gunsmiths to develop the craftsmanship to allow them, like Nelson, to let their passion meet their purpose.

The Gunsmith, Inc.

North Village Plaza

10210 N. 32nd St.

Phoenix, AZ 85028

https://www.thegunsmith.com

(602) 992-0050

— Greg Moats