Today’s feature is from correspondent Dave Spaulding.

I'm often startled when I wake up and realize how old I am. It seems like just yesterday that I was a young cop wanting to confront bad guys at every turn. In those days, I used to look at the older guys and think they were out of touch, with nothing but old and out-of-date information to offer. How wrong I was! Just because something is old doesn’t mean it’s out of date. Often, it means that it's proven in conflict and I’ll take a proven technique or tactic over something new and noteworthy every time.

Remember, fighting is final. If you engage in combat, you run the risk of being hurt or killed. It’s not a video game. There is no way to engage in nice fighting. There is no room for “politically correct” in this arena. I fear that some American cops and armed citizens have reached a time when force is preferably “minimal” instead of “objectively reasonable.” On the other end of the spectrum, some want to use military-style, battle zone tactics in domestic conflict. The U.S. Supreme Court has ruled in several landmark cases – and it’s written in many state statutes -- that force must be reasonable, but how many cases do you know of in which police officers used reasonable force only to get thrown under the bus?

You don’t think it could happen to an armed citizen?

What’s Old Is New

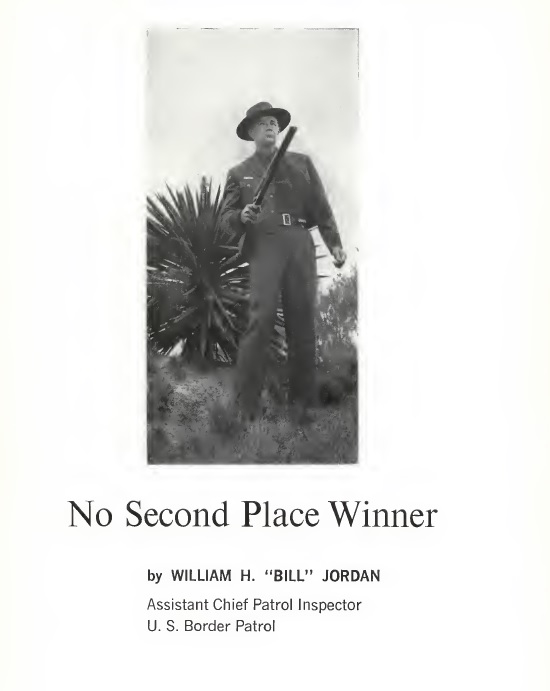

Landmark work by real-world experts of the past – like NO SECOND PLACE WINNER by Bill Jordan – contains lessons which have been built upon since their passing. Just because something is “old” doesn’t mean that someone hasn’t ‘repackaged’ it.

|

A number of years ago, I created a quick test anyone can use to evaluate any tactic or technique to determine if it’s worth learning, practicing and anchoring. I call it the “Three S Test” and while it is not absolute, it has proven to be helpful. First, is the tactic or technique simple to perform? If it's not simple to do on the range or training mat, do you really think it's going to get easier during a fight? Remember, we default to the level of training we have mastered and anchored, not just experienced. This means they’ll require more time and effort to use quickly and easily. Decide if it's worth it. Simple techniques are easier to learn, practice and master to keep sharp. Next, does the tactic or technique make sense to you? You're likely an adult with a wide range of life and work experiences, have formal education and task-specific training, maybe you were in the military or law enforcement and saw conflict. Maybe you are the victim of a violent crime and have adopted a “never again” attitude. If a technique doesn’t make sense to you, listen to your gut and ask the instructor about it. Finally, is the tactic or technique street proven? The instructor must be able to give you examples of where it's been used in actual conflict. One incident isn't enough. Be careful if the technique is named after the instructor, or the technique is the hinge pin of their entire program. No one should be a lab rat for someone’s whim or effort to make money.

Editor’s Note: Part II will appear next week.

— Dave Spaulding