Yesterday, in Shooting Wire, I covered shooting the double action revolver. Now for some gun handling hints. It’s simple – even easy, compared to shooting – but it’s hardly intuitive in my experience. It usually takes an old hand to show the way. Once learned, it seems easy to retain.

For loading and unloading, the watchword is gravity. It’s a constant and helps you in the process of loading and emptying a revolver. A question about Rule 2 arises, but it’s brushed aside as follows: when the gun is out of battery, it is unlikely to be able to fire. When you “disassemble” the double action revolver by opening the cylinder, pointing it skyward to help clear the empties from firing chambers is wise – unlike doing the same with an autopistol.

Keeping the gun level while dumping empties allows brass to get under the extractor star. This can be irritating on the range and a calamity on the street. “Let gravity be your friend.”

Loading is likewise aided by gravity. With the muzzle to the deck, loaded rounds can be guided to their chambers and Mother Earth does the rest … unless the gun’s very dirty.

The old unloading method was to simply open the cylinder, transfer the gun to the left hand (we were all right-handed then, I suppose), point it skyward and punch the ejector rod with the pad of the thumb. As state and local agencies went to magnums and federal agencies went to over-loaded 38s, the chamber pressures would form the brass to the chamber wall. The ejector rod would thus poke a hole through the pad of your thumb.

Not a good plan.

They moved to the “same thing only different,” by using the palm of the shooting hand to smack the ejector rod. Now the hole was through your palm and you could well have bent the ejector rod – again, less than profitable.

Worse, when shooting +P+ 38s or 357 Magnums, the first place to heat up on a revolver was the forcing cone – the aft part of the barrel that intrudes into the cylinder window of the revolver frame. The temperature would be high enough that officers in training were known to drop guns when the hand was unexpectedly burned.

I wandered into the Ayoob-Stressfire method; the gun stays in the shooting hand after the cylinder opens, the shooting thumb flagged high, keeping the cylinder still. Pointing the piece skyward, using the barrel as a guide, the palm at the proximal joint of the left hand firmly pops the ejector rod down, clearing the chambers.

I open the index and middle fingers of the non-gun hand (making a “V”) and cover the front of the cylinder with my hand, the ejector going between the first two fingers. The gun, now in the left hand, is pointed down, the revolver butt against my midsection. The palm of the supporting hand is cupped to catch loose rounds if fumbled. The dominant hand, the most dexterous, loads the chambers.

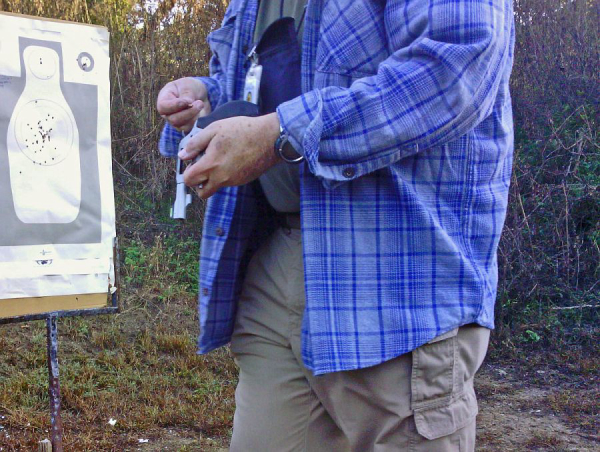

Traditionally – and by that, I mean when I went through the academy – ammo was carried in the strongside pocket on the range. To keep things moving, you’d simply load from the pocket with the gun a little less than level in the ‘wrong’ hand – as shown. Remarkably, this was relatively fumble free – whether from the intense week of firearms class or because it reflected how the human interfaced with the machine. Consider though that each round is individually being pressed into a chamber; using speed loaders, having the revolver being reloaded at an angle is a bad plan.

As I don’t carry loose rounds in my pockets, I’ve not practiced this since 1978.

A critical point to repeat: I pin the gun to my midsection as I load. This keeps things still, in a place that is kinesthetically repeatable in case I’m in the dark or something draws my attention from loading. This is where fluted cylinders are critical. You can load by feel, turning the cylinder back one or two places after filling – so those are the next chambers up.

Smooth, unfluted cylinders are worthless on a working revolver. Sadly, some manufacturers like them.

Do I prefer loops, loading strips, speed loaders …? Yes, I do. Any of them work with practice. I recently received some gear from Zeta6. Pictured is the J-CLIP. Designed for 5-shot 38/357 J-frame size revolvers, it features a pentagon shape which assists in fit and helps clear the stocks. The J-CLIP is made from polyurethane material for use in both hot and cold environments.

It looks interesting and I’m trying it out now.

-- Rich Grassi