It’s not just about guns, OC or other gadgets – and it’s not just about taking “hands-on” training. While physical skill and the appropriate tools are important, there’s more. It’s getting your mind right.

The fastest shooter with the mechanically best blaster doesn’t always have the edge on someone who has that preparedness component online. One of the best ways is to attend a presentation by someone who’s knowledgeable about staying alive in unfriendly places.

Another is to read a book.

I have a pair of texts I keep side-by-side. One is Defensive Living: Preserving Your Personal Safety through Awareness, Attitude and Armed Action – written by friends Dave Spaulding and Ed Lovette. The other is Principles of Personal Defense by Jeff Cooper. These small volumes comprise the extent of knowledge about that software component.

That’s a bit of a bold statement, but it’s not hyperbole; while some readers have complained about one or the other “lacking detail,” the point is that it is about getting your mind right. If you do the work, the detail fills in. This happens through practical application – doing it every day, making it a habit.

You have plenty of habits, you must know how to form them.

Being verbose won’t help.

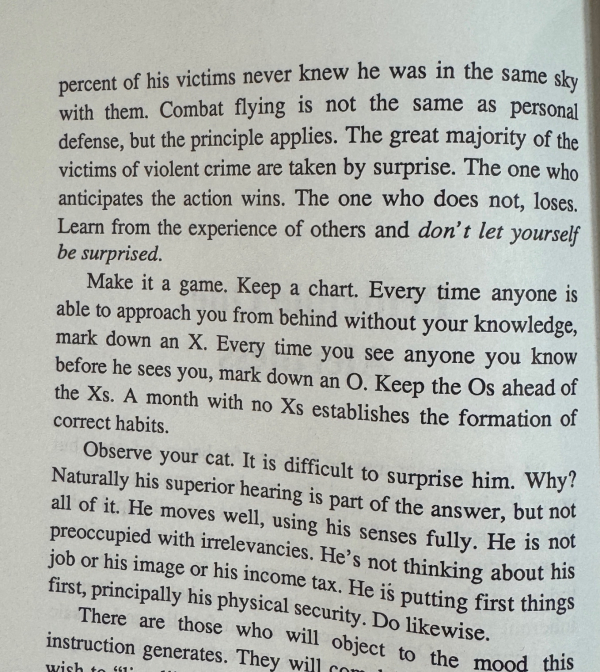

When Ed Lovette writes of playing “the game of Xs and Os,” he’s referring to Principles of Personal Defense, where that game is discussed under “Alertness,” Principle One. Alertness is first because it’s foundational; the other principles don’t come into play without it.

Absent this principle, you’ll be startled, surprised. Better is “Ah, I knew it! Here it comes.”

Officers who have been debriefed after an officer involved shooting report that it’s more “Ah, hell! – it had to be me.” Those who would have reported “No one was more surprised than I …” are often not available to fill in details.

A lack of “I could see it coming” is a critical flaw. There are times it’s not the end of the world – but that’s because the attacker lacked competence, you possessed luck, or some combination of the two. It happens, but it’s not to be relied upon.

Lovette’s time with CIA was partly spent ensuring that employees and State Department personnel kept their heads up and eyes open when deployed overseas. That’s a thankless job and the examples of failure to keep up are numerous. They make for negative examples, a few of which you find in the book.

But you don’t have to be deployed forward. Next time you’re stopped for a traffic signal, just look at the driver next to you. Chances are superb that the driver is engrossed in the phone, adjusting the rear view mirror and engaged in preening behaviors or just zoned out.

Then you need to look behind you. How long has that car been behind you? Is that someone following you?

To stay with the automotive examples, I was making a left turn off a boulevard onto a service road between strip malls a few days ago. The young lady in the car at the stop sign on the service road never saw me turn in front of her or drive by. As she was stopped at the traffic sign, her face was down and she was examining a personal communication device.

The number of times I’ve waited behind people stopped at a green light approaches the dollar figure of the daily accumulation of national debt.

Another example was from a household surveillance video. An example of “jugging,” it was said, the individual who’d just driven home was followed by a vehicle that was shortly assisted by another going the opposite direction.

As the victim backed in the drive, offender #1 pulled up, attempting to block the drive. Offender #2 pulled up facing Offender #1. Both vehicles emptied, armed subjects rushing up to contain the victim-driver who had just come home from a stop at an ATM. The offenders figured it was a withdrawal, not a deposit.

The victim was able to drive out and around them.

The lack of criminal success in this event was because of nothing the victim did – and that’s a problem.

You let them follow you home.

So, the lesson from both books – and this is just one – is to keep your eyes open. Learn to look for trouble – not so you can intervene but so you can avoid the need for your intervention.

That’s just the first short segment of each of these books – and why I keep them side-by-side on the shelf. I go back to them periodically and reread them. I try to get my mind right because anyone can get out of practice – as I proved just this week.

— Rich Grassi