Lest we forget …

When there’s an outrageous event, a tragic moment, a time where nothing seems to go right, it’s the lot of those who follow to answer the questions, “What did we do wrong?” and “How do we keep it from happening again?”

In the current era, police survival training is seen as “militant,” not appropriate for communities who fantasize that psych-social workers will more effectively mediate domestics and respond to calls to help people behaving in bizarre ways. But it wasn’t that long ago that two hoods massacred four highway patrol officers on a car stop in California.

The officers weren’t surprised by the potential for danger; they knew it risky as they were dispatched to check on a motorist accused of “misdemeanor brandishing” of a revolver. The call indicated that it was a single offender in the car; in reality, it was a pair recently released from prison who were arming up to do an armored car robbery.

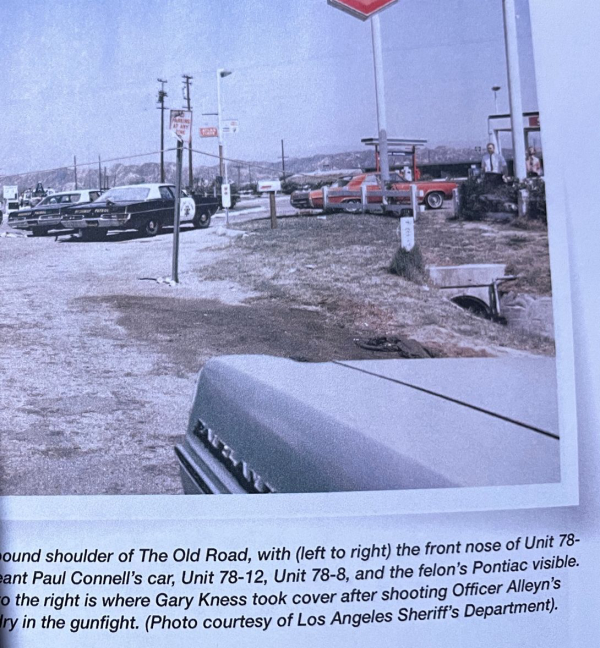

Other units were in the area at the time of the stop. One was close enough to cover when, alerted to the patrol car behind them, the hoods suddenly exited the interstate and parked just inside the driveway to a café/service station. This delayed the second car’s response.

The offenders were ordered out of the car, a Pontiac. The driver, after some prompting, complied. Unknown to the officers, he was wearing the Airweight Bodyguard he’d threatened another driver with just twenty minutes or so before. The passenger stayed in the car.

The driving officer approached the suspect who’d gotten into the leaning search position on the car. The passenger officer, armed with a shotgun, approached to physically remove the passenger offender from the car.

As the trooper opened the passenger door of the Pontiac, the passenger shot and killed him with a 357 Magnum. He continued his turn to shoot at the driver-officer across the car.

That officer fired at the passenger, but his closer suspect drew his snub revolver and shot the trooper twice, killing him.

Just then the support car was arriving and immediately came under fire from the felons.

I’d describe the mess that followed, but let it suffice to say the CHP lost two more troopers. The offenders were tracked, one captured and another holed up in a residence, later to commit suicide.

A word about analysis of these events. We’re not there, seeing what the participants and witnesses saw. If we were, we’d be at risk, likely surprised by the ferocity of the attack. Our perceptions of the event would be altered by that fact – just like the witnesses who were later interviewed. The later phone contacts, one between the captured felon and the barricaded suspect, were monitored, helping to piece together the event.

In the four-and-a-half minutes it took from the time of the stop for units to respond, a heroic citizen stopped to help and took up an (unknown to him) emptied shotgun. He jettisoned the empty gauge and seized the officer’s revolver, putting a hit on one of the felons – then had to retreat as the revolver was now empty. A wounded trooper, down behind a car, tried to reload his revolver from a dump pouch. One of the offenders circled around the car and executed him.

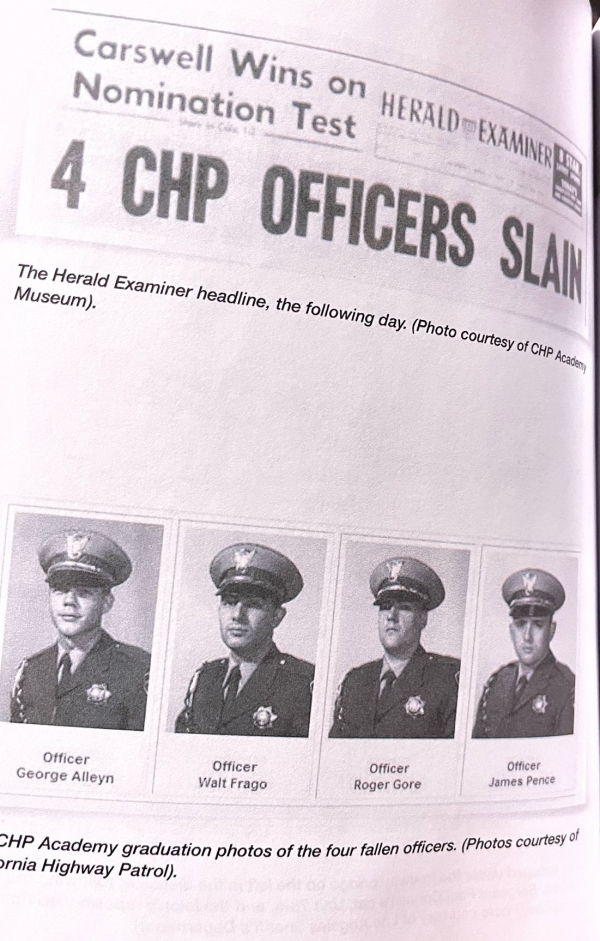

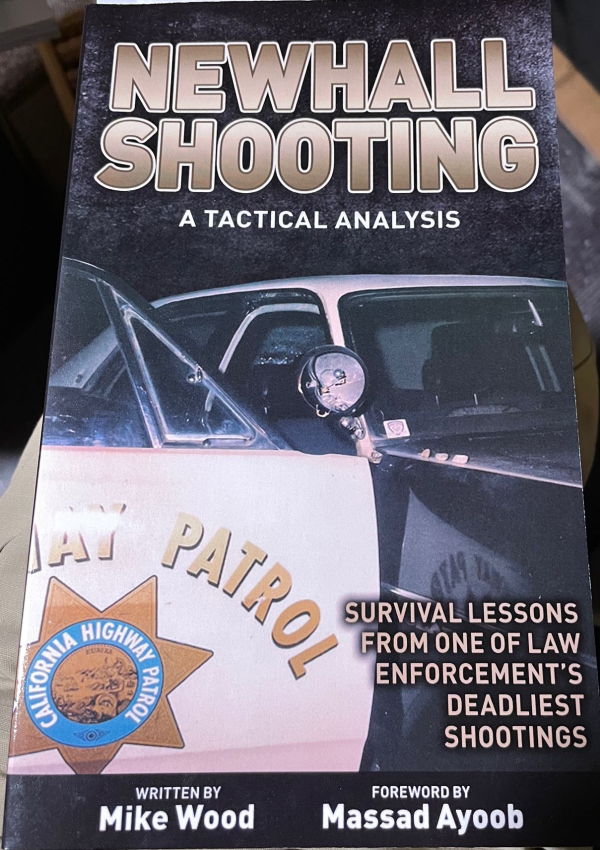

This happened in Newhall California, 1970. The book that does the best job of describing the incident, through to its resolution and discussing changes in equipment and training that followed, is Michael E. Wood’s Newhall Shooting: A Tactical Analysis.

Available from Gun Digest Books, this work is detailed, well-researched and it provides valuable lessons. It also serves to debunk some of the ‘shorthand’ explanations for why we train the way we train.

When detail is lost, the lesson loses value.

Aside from the fallibility of recollections of witnesses, Wood points out that events like these have multiple moving storylines, with each participant taking an active and sometimes confusing part. Trying to piece the event together is rigorous.

The book is well worth the study, particularly for current members of service. Lessons learned with bloodshed have been forgotten. If you think that 17-shot autoloading pistols, gun-mounted lights and optics and soft body armor make this easier, think again.

It ain’t the gear, it’s the brain. And no brain is prepared for an event like this without training, practice and sustainment – to kind-of quote an Oklahoma lawman.

Wariness is order of the day. If you try to stop a car and the occupants choose the location they stop, it helps to ask yourself “why?” If the report is “a motorist in a Pontiac pointed a gun at another driver” and you get behind the offenders’ vehicle and see two people, it should be a red flag. It may mean nothing but a confused complainant or a dispatcher got it wrong – but be suspicious.

If it’s a “gun call” or something else that doesn’t seem right, don’t take chances. Ordering the driver out over the PA on your car – and then approaching him – is likely not a good idea. Consider not stopping the car at all until other units are in place to gain situational dominance.

Practice contact-cover tactics; one of you does all the talking and will do any necessary approach as needed, while the other stays back in a protected position ready to offer deadly force should the need arise. Consider it overwatch.

There was a lot made about Officer Pence reloading his revolver all the way up with loose cartridges from a dump pouch – taking time that allowed the offender to approach to close range to kill him. There were stories circulating that empty brass was found in a dead trooper’s pocket because they didn’t let them dump brass on the ground when on the shooting range – without basis.

The CHP of the era shot 38 Special ammo on the range – wadcutter – and were issued the 158gr lead round nose for duty, but they allowed troops who bought their own 357 Magnum revolvers to load them with personally purchased Magnum ammo. The disparity of blast, recoil and – likely – point of impact shifts between the light loads and the magnums, could combine to allow too many misses.

The distance from the front of the first responding car to the offenders’ vehicle at the scene was only fifteen feet. Far too close; distance was clearly not a factor favoring the trained or prepared. The offenders made better use of cover and concealment – as well as movement.

Neither the officers nor the offenders scored hits at any real distance. The felons used surprise and rapid aggressive movement to close the distances so they could hit. The only serious shooting was done by the citizen who tried to help. He said he used two hands to steady the downed officer’s revolver and fired it single action. Still, it appears the round skipped from an auto body and the jacket from the bullet struck the offender, causing him to break off his attack.

That and a single buckshot pellet that was nearly spent from an impact with the Pontiac that went on to hit the felonious driver in the forehead were the only hits scored on the bad guys. (It didn’t disable him.)

We need to learn from those who’ve trod the ground before us; they learned lessons that are passed on. Failing to learn from those lessons is an act of disrespect for the fallen.

Don’t make their mistakes. They paid for it so we wouldn’t have to.

Read the book.

-- Rich Grassi