I got into the firearms instruction game early in my career, actually getting into the state academy’s instructor school in 1983, just prior to getting on at the Sheriff’s Department. Much of the handout material came from NRA Law Enforcement and it was a terrific school. I learned a lot of what was known from 1948-1970 or so – but no farther.

That’s not a criticism, just history. Everyone’s in a straight line shooting on full-size (plus) silhouette targets, par times for cylinder dumps followed by reloading. That’s after you arrived with an empty gun (wink, wink) because loaded guns are ‘unsafe’ on ranges. There were scores, percentage of possible, hits on the ‘line’ counts the next value up. Low on ‘officer survival,’ long on “don’t shoot yourself” and “high enough score means you pass.”

After I’d joined the S.O., they began the transition to semiautos in 1986 and they sent me back to the academy to refresh my instructor training to assist in the agency transition. It was two weeks now instead of one. I’d been reading Ayoob’s book Stressfire and one of the academy staffers, a young fellow at the time, absorbed it quickly.

A few years later, the outfit sent me to an NRA instructor school local to us. It was a week long, well enough done. I noticed that the handouts hadn’t changed from my 1983 class and it was pretty typical stuff. Long on basics – good, short on teaching people to fight with guns.

After I met Massad Ayoob, things changed quickly for me and one of the aspects was national trainer membership in ASLET and teaching nationally. There I met Clive G. Shepherd.

To say I was mesmerized by his teaching style is an understatement. An expat, he was a veteran of Royal Marines, a Colour Sergeant … yes, I had to look it up too. He fled the miserable weather of his home country in the Marines, then fled for the United States. Taking shelter in Miami, he began his firearms instructing there with the influx of people seeking permits under the new “shall issue” program. He came to the attention of NRA, who asked him to come aboard to teach police instructor trainees.

He evaluated the program and began instituting changes that resulted in the Law Enforcement Activities Division the crown jewel of readily available instructor training for police agencies.

Starting in his usual style, he’d smile at the class. After a short introduction, he’d go into the routine.

“By now,” he’d drawl, “you’ll have guessed that I’m not from these parts.”

Smiling, he’d wait for the laughter to die down.

“And I’m not from Australia, before you ask. It’s a penal colony!”

He was strict about applying the training -- the rehearsal -- to the mission. “It’s not close with and destroy the enemy,” he noted. “For you, it’s protect and serve.”

You may have to fight with guns, to save your life and the life of others you’re responsible to protect – but teaching soldier stuff isn’t quite the answer. “We have to be selective of our techniques and gear our training to serve the needs of our students.”

Clive was heavy on the service aspect of training. Students want to know why we teach something. Their time is valuable.

How much value do they get for the next hour of instruction?

How much value do they get from the next fifty rounds of ammunition?

If you can’t answer those questions, you’re in the wrong business. We have expectations from participants: safety – they’re part of the safety staff, active participation, punctuality, a desire to learn & improve. As to instructors, they’re to be role models. “We lead by example, we are responsible. We teach them to win the fight and to go home alive.”

Why do we teach a particular component? It’s not “This is the way we’ve always done it,” or “This is the way I was taught.” It’s not “This is the way Fred said to do it.” (Fred is the cut-out of a skeleton with badges on it; the prototypical student.)

It is, “I think this is the best way for my students.” How do you find out? Try new stuff on the range. You read, you become a student in other classes.

He drove classical range masters crazy; he’d clutter up the range, use home made 3D targets, having people move about with guns in hand. Clive taught how to shoot around cover, not from a ‘barricade’ (which is competition-speak). He taught running the gun one-handed, proposed that instructors should be able to teach and function with either hand – some of the students are ‘wrong-handed,’ and we’re as responsible for them as the others.

As a noncommissioned officer, he was fine at being controversial. “Out to ten yards,” he’d say, “sights are overrated.” You’d think it was Rob Leatham with a distinct British accent. He decried the “Mickey Mouse accuracy tests” and, questioned about ‘qualification,’ would say “Qualified? To do what?”

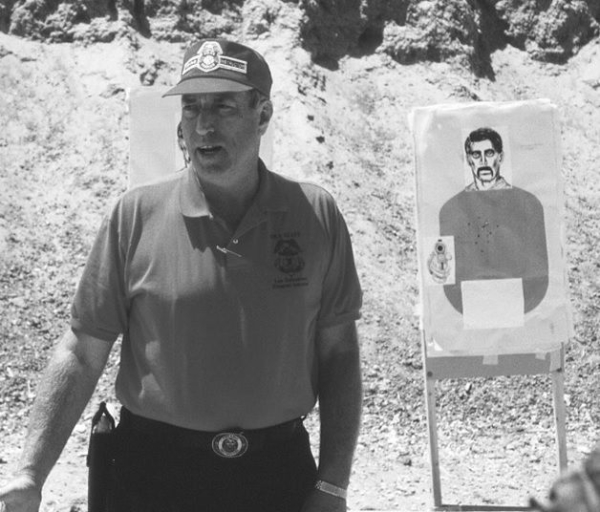

He’d doctor up targets. Responsible for the latest iteration of the NRA LEAD target, he’d put photocopy faces on them, put a sheet of printer paper in landscape orientation on the lower part of the silhouette and put a ‘gun’ image on the target – some held right-handed, others left. You’d heard him call out when it was time to change targets. “Remember to get faces, guns and groins.”

The objective was to get the fight over quickly. The reason is so you are shot less. He assumed that “bullets don’t work,” and when someone would object about the ‘get shot less’ statement, he’d smile.

“If you’re in a physical struggle with an offender, you figure you’ll get hit? Yes? If you struggle with someone who has a knife, what chance you’ll get cut? 100%? Probably? Okay, so if you’re in a shootout, it’s entirely likely you’ll get shot. You’d best accept that and move on.”

In 44 hours, he’d pack in years of instructional skills, non-standard shooting exercises, how to move with gun in hand, how to move around others with gun in hand – it’s like taking service schools from the former industry schools (HK International Training Div., Beretta, S&W Academy) while sprinkling in some Clint Smith, Mas Ayoob, and more. It was a deep well.

Clive Shepherd traveled with this trunk of gear for most of the year. He’d ship the trunk to a venue, fly out Sunday, train, ship the trunk Friday to the next location, get home long enough for laundry and to express mail supplies to replenish the trunk, then fly out Sunday to the next gig.

He wasn’t vastly impressed with working for NRA (“The great thing about it is that you can always find a better job,” he’d say). He was clearly impressed by the attention and dedication of the people he worked for. They were his reason for making the effort.

Clive Shepherd left the place better than he found it. I missed his death notice from 2017 and that of his beloved wife in 2018.

Fair winds, Marine, and following seas. You made a difference. There are a number of us who won’t forget.

-- Rich Grassi